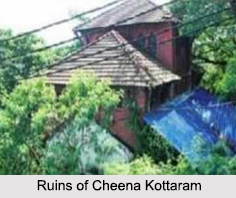

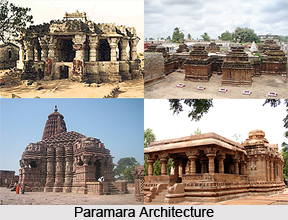

The Paramaras, founded in the northern Deccan domain of Malwa and expanding to the borders of Rajasthan, were amongst the most important successors to the Pratiharas. The Paramara architecture in India reflects distinctive Bhumija style that appears early in the period of their predominance. One of the earliest masterpieces of this style is the Nilakantha or Udayeshvara at Udaipur, Rajasthan of the mid-11th century king Udayaditya. Interestingly, the Paramara architecture was also exposed to exotic influence from the south.

The Paramaras, founded in the northern Deccan domain of Malwa and expanding to the borders of Rajasthan, were amongst the most important successors to the Pratiharas. The Paramara architecture in India reflects distinctive Bhumija style that appears early in the period of their predominance. One of the earliest masterpieces of this style is the Nilakantha or Udayeshvara at Udaipur, Rajasthan of the mid-11th century king Udayaditya. Interestingly, the Paramara architecture was also exposed to exotic influence from the south.

The Udayeshvara has a `mulaprasada` with seven bays to each side but the projections, treated as piers bearing many aedicule, radiate like the points of a star within a circle. Aligned on the principal axis are a vestibule, a nine-square closed hall expanded to form a cross with three porches, and a detached pavilion. The decorative details are idiosyncratic. Above the entablature the seven-storey shikhara has five vertical rows of miniature shikharas on pillars between delicately carved bands of meshed miniature niches which rise from extremely elegant dormers over the `ghana-dwars` and the magnificent vestibule gable. The roof of the hall is a variant on the `Samvarana form`, which is by now has become familiar in the state of Gujarat. The pillars are multi-faceted with extremely elaborate niches on the principal facets and fantastic brackets superimposed over multiple rings; the pillars above the porticos are notably short but there is space for great elaboration. There are triple-jamb portals to the hall but the sanctuary portal has five bands including an architectonic one with spiral scrolls and a beam of niches.

Due to dynastic ties, perhaps, Maharashtra preferred the Bhumija style found in Paramara architecture at the same time as its most prominent manifestation in Malwa. The Ambaranatha Temple at Ambarnath near Mumbai is the Udayeshvara`s superb contemporary style. However, there are important differences. In the first place, the the temple`s closed halls are commensurate squares aligned orthogonally but as their corners are cut back to form equilateral projections repeated for each porch, they appear to be disposed diagonally in plan. Secondly, apart from the absence of quadrant curves in the superimposed tiers of the shikhara`s intermediate zones, the piers are more significant than the highly unorthodox miniature shrines they support. Further, the hall`s Samvarana reflects the influence of Gujarat as does the base with elephant frieze. On the whole sumptuous faceted columns define the central space of the hall with its dazzling ceiling, but various square forms are used elsewhere and the portal jambs reveal some influences of architecture of Chalukya dynasty, though the lintel is of the Gujarati type.

Interestingly, in the entire process of synthesis of elements from north and south the Ambaranatha temple was visionary of the Deccani style which was to be fostered by the Yadavas of Devagiri, who succeeded the Rashtrakutas dynasty in the heart of their domains around Aurangabad, and progressively expanded their holdings in the north Deccan at the expense of the Chalukyas. Active from the second half of the 11th century in a region that was virtually a cultural province of Malwa. Their extensive corpus is represented by the Gondeshvara of their capital, Sinnar. The Sinnar work reflects the influence of both Udaipur and Ambarnath. Star-shaped `mulaprasadas` appear at other Yadava sites. Like for instance Lonar, where the hall of the Daitya Sudama is an enlarged variation on the theme of the mulaprasada. The Malwan pattern for closed halls, followed at Sinnar, was perhaps the Yadava norm but the predominantly extravagant fifty-columned open one at Anwa, with a central space defined by twelve great faceted columns and covered by a superb concentric ceiling, bears comparison with the one at Modhera.

Interestingly, in the entire process of synthesis of elements from north and south the Ambaranatha temple was visionary of the Deccani style which was to be fostered by the Yadavas of Devagiri, who succeeded the Rashtrakutas dynasty in the heart of their domains around Aurangabad, and progressively expanded their holdings in the north Deccan at the expense of the Chalukyas. Active from the second half of the 11th century in a region that was virtually a cultural province of Malwa. Their extensive corpus is represented by the Gondeshvara of their capital, Sinnar. The Sinnar work reflects the influence of both Udaipur and Ambarnath. Star-shaped `mulaprasadas` appear at other Yadava sites. Like for instance Lonar, where the hall of the Daitya Sudama is an enlarged variation on the theme of the mulaprasada. The Malwan pattern for closed halls, followed at Sinnar, was perhaps the Yadava norm but the predominantly extravagant fifty-columned open one at Anwa, with a central space defined by twelve great faceted columns and covered by a superb concentric ceiling, bears comparison with the one at Modhera.

In general, as at Sinnar, Gujarati patterns are displaced by an essentially Deccani one, mainly square in section with recessed octagonal or circular bands and sometimes with a `purana-kalasha` interpolated well below the graded rings and padmas which form the capital. The Gondeshvara has a single wall painting but the most ambitious Yadava temples reflect the style of Solanki architecture in India. The much-mutilated but once-splendid Naganatha at Aundha incorporating no fewer than four friezes. After the Gujarati pattern, one register of iconic sculpture is the norm but the Gondeshvara is unusual in its class in having applied pillars and other abstract motifs instead of figural relieves in most of its aedicule.

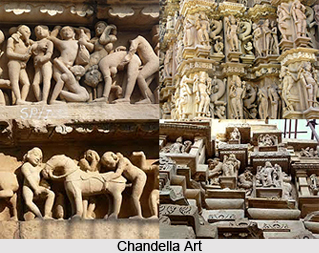

The Paramara architecture in India also reflected Bhumija manner that rapidly spread east and west, reaching the Kalachuris by the end of the 11th century and being taken up even by the Chandella dynasty for their last notable work at Khajuraho temples. Here miniature `Sekhari shikharas` are superimposed over subsidiary equilateral projections aligned on the diagonals between the cardinal ones. This experiment in Sekhari or Bhumija cross-fertilization was not a happy one, however without balconies; the orthogonal could not compete with the diagonals and seem to provide inadequate support for the weighty half-shikharas. The Chandellas` marked ability to affect a monumental balance between whole and parts had been lost.

Bhumija style is quite rare in Gujarat but in Rajasthan it was considered as an important ingredient of the hybrid style which the Rajasthanis forged between the 12th and 15th centuries from components provided by all the major post-Pratihara schools. The Shiva Temple at Ramgarh is an early Bhumija hybrid, the Surya Temple at Ranakpur reflects Bhumija pattern. The former has bands of enmeshed niches over both principal and intermediate projections, separated by pillars bearing two distinct types of miniature shikharas. The Ranakpur Surya Temple has a unique `mulaprasada` with eight major projections separated by triads of minor ones. Above, miniature shikharas half mask the mesh bands in the Sekhari manner in contrast to the tiers of still smaller ones which fill the adjoining zones in the Bhumija approach. Though such cross-fertilization is a rare thing in itself, it is nonetheless characteristic of the prolix inventiveness of the Rajasthani imagination.