The first step in the process of linguistic reorganisation of states occurred in the after effects of a major movement in the Andhra region of the old Madras province. This led to the appointment of the States Reorganisation Commission which published its report in 1955. Subsequent to the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, the boundaries of the southern states were reorganised in closer conformity with traditional linguistic regions. The split of Bombay province into the present states of Gujarat and Maharashtra followed in 1960. In 1966, Punjab was reorganised and its several parts distributed among three units: the new state of Haryana, the core Punjabi Suba, and Himachal Pradesh. A number of new states also have been curved out in response to tribal demands in the north-eastern region of the country from time to time. The most current addition to the states of the Indian Union occurred in May, 1987 with the transformation of Goa`s status from that of a union territory to India`s 25th state. All the reorganisations except those in the Punjab and in the north-eastern region of the country have satisfied the grievances of the principal large language communities of India.

The first step in the process of linguistic reorganisation of states occurred in the after effects of a major movement in the Andhra region of the old Madras province. This led to the appointment of the States Reorganisation Commission which published its report in 1955. Subsequent to the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, the boundaries of the southern states were reorganised in closer conformity with traditional linguistic regions. The split of Bombay province into the present states of Gujarat and Maharashtra followed in 1960. In 1966, Punjab was reorganised and its several parts distributed among three units: the new state of Haryana, the core Punjabi Suba, and Himachal Pradesh. A number of new states also have been curved out in response to tribal demands in the north-eastern region of the country from time to time. The most current addition to the states of the Indian Union occurred in May, 1987 with the transformation of Goa`s status from that of a union territory to India`s 25th state. All the reorganisations except those in the Punjab and in the north-eastern region of the country have satisfied the grievances of the principal large language communities of India.

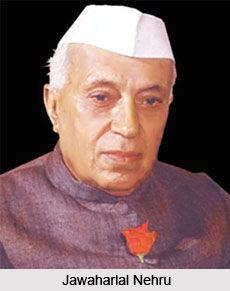

Several Indian leaders announced their goals after Independence to be the establishment of a strong state, to which all the miscellaneous people of India would transfer their principal loyalties and immerse their cultural differences in a uniform nationalism. Others, to some extent more attuned to the realities of India`s varied cultural differences, thought a "composite" nationalism would emerge combining aspects from the cultures of the various major religious, linguistic, regional and tribal peoples. Out of the disagreements which developed between the central government leaders, with their ideology of a strong state and a homogeneous or composite nationalism to support it, and the successive demands of leaders of language movements for reorganisation of the internal boundaries of the provinces, a set of rules and a general state policy emerged which were more pluralist in practice than the ideology, which appeared integrationist. In effect, the Indian state during the Nehru period took on the form of a ethnically pluralist state, in which a multiplicity of major peoples, defined principally in terms of language, were recognised as corporate groups within the Indian Union with rights equal to all other such groups.

Recognition on the institution of equality did not extend to all the culturally distinguishing groups or even to all the large language groups in India, but only to those language groups which were competent to justify a claim to dominance within a particular region of the country. Such substantiation, for the most part, could be made good only by those groups, whose languages had already received some official recognition under British rule and had undergone some grammatical standardisation and literary development, often involving the absorption of local dialects, and had become well-established in the government schools in their regions. The leaders of such language groups were well placed to launch the various movements which occurred, particularly during the 1950s and 1960s, for linguistic reorganisation of the Indian states. In the course of these struggles, the central government developed a set of four formal and informal rules, whose application led to the recognition of the supremacy of some language groups and not others in major regions of the country.

The first rule was that the central government would not identify groups which made secessionist demands, but would repress them by all means necessary, including armed force. That rule has been applied to various tribal groups in the north eastern part of the country since Independence, where the Indian Army has been engaged in more-or-less continual warfare with and containment of the secessionist demands of Nagas, Mizos, and others. The second rule is that the government will not accommodate regional demands based upon religious differences. This rule was applied chiefly to the Punjab, the last large Indian state to be reorganised in 1966. The government of India resisted the linguistic reorganisation of the Punjab more effectively than it did the reorganisation of the former Madras and Bombay. One important reason was the primary perception that the demand from the Sikhs for a Punjabi speaking state was simply a cover for a demand for a Sikh majority state.

The third rule was that demands for the creation of separate linguistic states would not be approved capriciously or on simply "objective" grounds that a distinctive language was the major spoken language in a particular region. This rule developed out of the general unwillingness of the central leadership to divide the existing provinces rather than out of any clear principle. Thus, there was a demand from politicians from western Uttar Pradesh in 1954, supported by ninety seven members out of hundred in the Legislative Assembly of that province, for the establishment of a new province out of western Uttar Pradesh and the then Haryana region of Punjab, but which had no noteworthy popular basis, and was never taken gravely by the central government. The fourth rule was that the central government would not consent to reorganisation of a province if the demand was made by only one of the important language groups concerned. The reorganisation of the southern province of Madras was taken up first in the procedure of linguistic reorganisation partly because it had strong support from both the Telugu- and Tamil-speaking peoples. However, the reorganisation of the former Bombay province was postponed for a number of years because the demand came mainly from the Marathi-speaking region and was opposed in Gujarat, where for a time it was felt that the loss of Bombay City was too high a price to pay for a separate Gujarati speaking state.

Under Jawaharlal Nehru, the reorganisation of the southern states and of the Bombay province was carried out productively through the application of these rules. The way the process was carried out also led to a particular kind of balance in center-state relations, in which the Center avoided placing itself in a position of confrontation with influential regional groups but instead adopted a stance of intervention and negotiation between contending linguistic and cultural forces.