The importance of food in Bengali culture has always been most evident. There are direct depictions of food in art, in painting, literature, cinema. Conversely, there is the artistry of preparing and presenting food. But all such convergence of food and art, however sublime, is about food as an object of consumption and sustenance, either in the immediate present or savoured as a memory or anticipated as a future pleasure. But there is a third dimension, where food is the medium for depicting the emotional, ceremonial and ritual universe of a people. It is a realm where, having already experienced the pleasures of preparing, presenting and partaking, one has subsequently made it into a versatile medium for both spiritual and artistic creativity, a metaphor for diverse human experiences. As in, the simple and complex conjunctions of food and art among the Hindus of Bengal.

The importance of food in Bengali culture has always been most evident. There are direct depictions of food in art, in painting, literature, cinema. Conversely, there is the artistry of preparing and presenting food. But all such convergence of food and art, however sublime, is about food as an object of consumption and sustenance, either in the immediate present or savoured as a memory or anticipated as a future pleasure. But there is a third dimension, where food is the medium for depicting the emotional, ceremonial and ritual universe of a people. It is a realm where, having already experienced the pleasures of preparing, presenting and partaking, one has subsequently made it into a versatile medium for both spiritual and artistic creativity, a metaphor for diverse human experiences. As in, the simple and complex conjunctions of food and art among the Hindus of Bengal.

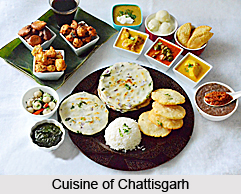

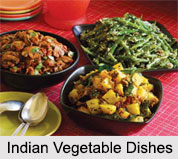

The traditional life of Bengal is rich in form, ritual and aestheticism. In sacred and secular ceremonies, Bengalis have invested food with intricate symbolic significance. An extraordinarily active folk imagination draws on food images to create verse, paintings and craft objects. Food, whether in its raw form or modified through human preparation, runs as a constant motif through these modes of artistic expression. In the rural background, it provided the raw material for painting and making offerings to the pods; it enhanced personal experience when its shape, colour and life became metaphors for human existence; it acquired symbolic meaning and enriched social customs with ceremonial value.

The intertwining of food and culture is seen in almost all aspects of life in Bengal. In the domain of art, it is seen reflected in the various forms of paintings and literature of the region. A marked example of this can be seen in the Chharas, which are literary compositions. These mainly deal with domestic life and have mostly been composed by women, Almost all the Chharas deal with food and its various aspects- they talk about the preparation of food, how it is acquired or bought, the ritual significance of food, the various types of dishes prepared and so on and so forth. Even in the realm of painting, the colours used for paintings, as in the case of the Kalighat pats, the themes of the paintings and even the material used for the same, all utilize food in one way or another. Alpanas are decorative patterns made on the floors of Bengali households during festive occasions or celebrations. Even these are food-based as the alpanas are made out of rice paste.

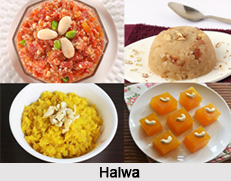

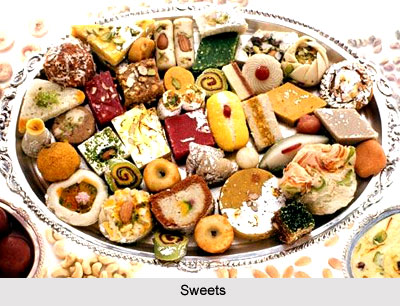

In the religious arena too, no rite is complete without the presence of food. It is offered to the Gods to appease them and food stuffs like rice and fruits are a must in almost all the ceremonies. No puja or act of worship is complete without the making of offerings, however simple or meagre. Rice, as expected, is an integral part of such offerings. Unhusked rice and trefoil grasses are presented to the deities along with whole and cut fruits and other foods.

In the religious arena too, no rite is complete without the presence of food. It is offered to the Gods to appease them and food stuffs like rice and fruits are a must in almost all the ceremonies. No puja or act of worship is complete without the making of offerings, however simple or meagre. Rice, as expected, is an integral part of such offerings. Unhusked rice and trefoil grasses are presented to the deities along with whole and cut fruits and other foods.

In festivals and rituals too it comprises an important part of the various ceremonies being performed. A common Bengali adage refers to thirteen festivals in twelve months. Festive rituals abound throughout the year and vary sometimes even from family to family. The festivals range from the strictly religious (the worship of specific deities in the Hindu pantheon) to the semi-sacred (the observance, usually by women, of certain auspicious days in the lunar calendar, or the practice of rituals in connection with a brata or undertaking/vow) to the entirely secular (weddings, birthdays, an infant`s first meal of rice, etc.). On all these occasions homes, whether rich or poor, are decorated with intricate patterns rich in symbolism and artfulness. This is known as the alpana. Traditionally, this is done by women and highlights an imagination based on an acute observation and appreciation of the natural world and its products. Feasting and cooking a great variety of food items are an important part of these rituals.