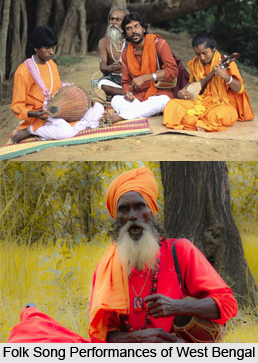

Features of East Indian folk music have various aspects to consider. It is generally contended that folk-music is composed of limited notes which occur spontaneously in the psycho-physical condition of a man isolated in a pocket or living together with others in rural areas in the lap of nature. Thus, topography influences him considerably in his composition. Tunes, as occur to him first, are limited in numbers, and far more notes occur as vehicles of worded expressions. Only a few phrases, depending on a limited number of notes thus devised, are constantly repeated. Once a few combinations of notes are made spontaneously by a single person or collectively, these are rhythmically arranged and constantly repeated, memorized and linked together with every-day vocal expressions. At length, these limited forms become the trait of a particular class or group, and the musical contour thus attained is passed orally from man to man. It is now proved by analysis that such music, represented in a few catches of notes, are generally limited to three to five notes.

Features of East Indian folk music have various aspects to consider. It is generally contended that folk-music is composed of limited notes which occur spontaneously in the psycho-physical condition of a man isolated in a pocket or living together with others in rural areas in the lap of nature. Thus, topography influences him considerably in his composition. Tunes, as occur to him first, are limited in numbers, and far more notes occur as vehicles of worded expressions. Only a few phrases, depending on a limited number of notes thus devised, are constantly repeated. Once a few combinations of notes are made spontaneously by a single person or collectively, these are rhythmically arranged and constantly repeated, memorized and linked together with every-day vocal expressions. At length, these limited forms become the trait of a particular class or group, and the musical contour thus attained is passed orally from man to man. It is now proved by analysis that such music, represented in a few catches of notes, are generally limited to three to five notes.

Notes of Folk Music

If folk-music adopts a system, it is a system of its own an unwritten, habitual and a naturally devised formation. Rural minstrels are seen to recite their songs even in one or two notes continuously with cymbals played by them. And, gradually, the execution of these two notes depends on a continuous process which relates to the voice quality of the singer. In East Bengal and Assam, some minstrels carry boxes containing the image of goddess Subachani (Sitala) and move from door to door singing eulogies only in two notes, though basic notes sometimes change along with the continuity of phrase. Numerous instances of one-two-three notes in music can be cited from typical devotional songs of the adivasis. Some of them may be observed to limit their music to three-four notes. Most of the brata songs of womenfolk are peculiar instances.

Dudhukigita and Ghodanacagita in Oriya, and Ojapali and a number of ballads in Asamiya may be cited as instances. Some of the Tibeto-Burman groups of men of the eastern hill areas use notes in almost staccato form, and naturally the graces and inflexions do not generally occur in these songs. But the people more in touch with urban areas tend to take occasional flights of notes, more than the fifth note in addition to some simple graces. Similarities in nature of tune all over the land and use of notes in limited number of phrases, thus, indicate the possibility of classifying music into some divisions.

Dudhukigita and Ghodanacagita in Oriya, and Ojapali and a number of ballads in Asamiya may be cited as instances. Some of the Tibeto-Burman groups of men of the eastern hill areas use notes in almost staccato form, and naturally the graces and inflexions do not generally occur in these songs. But the people more in touch with urban areas tend to take occasional flights of notes, more than the fifth note in addition to some simple graces. Similarities in nature of tune all over the land and use of notes in limited number of phrases, thus, indicate the possibility of classifying music into some divisions.

Tonal Quality of Folk Music

The classifications may be clearly had of the scales used in different groups of songs. Now, even if one finds the use of the same scale and the same number of notes in two different sections, differences in the formation of phrases and execution are remarkable features. There is no doubt that rhythm applied to songs and the total effect of combination indicates the specific nature of difference amongst different types. A few musical qualities pertaining to voice, tonal quality, grace and the nature of execution, though in very small degrees, are also to be considered in this regard.

Another relevant point that strikes most is topography and nature operates on the vocal tone and the manner of exposition. People originating from the same stock but residing in different environments altogether attain different types of tones and natural inflexions of notes.

For instance, people of Bengal in the East and West may be compared broadly. The Riverine districts and plains affect their voice to develop loud tonal quality of pitch notes with an element of sliding down the octave to lower notes. This becomes evident on an examination of Bhatiali. It is observed that these folk-songs are based more on top notes. The up-and-down dry lands of the west rouse in the singers a tonal quality in the middle octave of limited notes as in Bhadu songs and Tusu songs.

The people of the upper Brahmaputra valley and hills conceived yelling and loud expressions in musical forms, whereas those of the coasts of Odisha coasts combine a few notes in a peculiarly accented manner, primarily because of the impact of climatic conditions and environment. The same stock of men from Kashmir, migrating to the valley of the Ganga River, may be observed to have different tendencies in tonal productions, use of natural graces and composition of notes.

Some similar lines occur in the folk-music of Maharashtra and Bengal, but the nature of music differs due to performance of the rhythmic peculiarities of music with graces and inflexions, which occur partly at least due to natural conditions and the topography of the land where people live. This may, however, be treated as a general condition of occurrence of notes and phrases. Before going into particular instances, one may mention some points regarding the position of notes and phrases.

•In the recital of ditty, lullaby, proverbs, etc., a rhythmic continuity is produced by one-two-three notes, the effect being a few phrases embraced for musical repetition. It is a short piece with small tuning considered as recitation and not music.

•Similar recitative phrases composed of two, three or four notes are covered in recitation of long narratives like the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, etc., in which continuity of similar limited rhythmic phrases occur without giving it any impression of song.

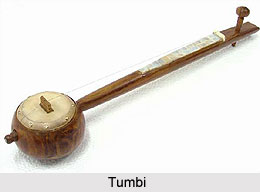

•Some tunes are made of three-four notes in one tetra chord; rhythmic music of a few phrases arranged in two lines makes it a complete tune. These repeating rhythmic groups in two lines make a complete music. Earlier, these forms were supported either by tala yantra (rhythmic instrument) or later by drone or tata-yantra (singing instrument).

•Forms of songs of various types, based on notes of upper tetra chords, are a peculiar feature. A few fixed musical phrases in two-four lines occur in two stanzas. The range of the tune covers the third or fourth notes of the upper octave.

•Songs, developed in full musical forms, are generally confined to two groups (stanza) of music-two lines consisting of the first group and two lines of the second. The first group embraces several phrases mainly based on the lower tetra chord, and the second group covers, in some instances, the three-fourth note of the top. These are considered to be the full-fledged folk-songs of the developed types having two movements.

•Some phrases of general types of songs (religious/miscellaneous) of two types cover nine notes of the two tetra chords and also three-four notes of the lower octave or three-four notes of the top (upper).

•There is a definite method for use of minor notes in phrases. Minor fifth or tivra-ma is never observed to occur in folk-songs. In any case, one has to focus attention more on phrases than individual notes, since songs with rhythm and lingual expressions are based on combinations of notes. In case of a recital based on single or double notes, it is the combination of note and rhythm that matters.

As mentioned above, the nature of tunes demands a clear classification of the method of notes used. The primary condition of the use of notes and their general arrangement in a few series, in every type of song, restrict songs to different section, which are called scales. And scales of folk-music, if defined through Indian principles, are limited in numbers. The general musical structure of songs needs to be described now, so that the major contour, naturally and spontaneously devised, may be followed easily in the illustrations (notations).

•Small songs and ditties have one or two movements of the tune; number of phrases in Bengali songs of the western sector are a very few only.

•General popular songs like Baul, Bhatiali, Sari, Bhaoaia, etc., are complete with two movements. Though songs are of longish patterns, tunes and phrases have slight variations. Burdens of songs are often attempted to be made attractive for being repeated.

•General narratives with one major stanza composed for repetition and refrain is normally put to a thin musical structure.

•Recitative items with two movements of tune have a very small musical frame. Musical variations of these different types of items depend primarily on rhythmic representation. Any slightest change in rhythm makes the same musical structure sound differently. Since long narratives possess the general musical peculiarity composed of a few commonly known phrases which occur in a similar method in other compositions, it may not bring about any new feature to be illustrated in details.