Cave architecture of Mauryan Empire the architectural remains usually ascribed to the Maurya period very few are artistically significant. The chaitya halls and the stupa do not exist in their original form except the excavated chaitya-halls, bearing inscriptions of Ashoka and Dasaratha, in the Barabar caves. The monolithic rail at Sarnath in grey and polished Chunar sandstone has been erected under the patronage of emperor Ashoka himself. Its architectural form is similar to the rails of Bharhut stupa and must have been literally transferred into stone from contemporary wooden originals. The plinth or the alambana, the stambhas, the horizontal bars and the coping have all been just carved out of what must have been a huge slab of stone. The altar or the bodhimanda situated at Bodhygaya is traditionally associated with Ashoka. The Bharhut altar consists of four pilasters.

Cave architecture of Mauryan Empire the architectural remains usually ascribed to the Maurya period very few are artistically significant. The chaitya halls and the stupa do not exist in their original form except the excavated chaitya-halls, bearing inscriptions of Ashoka and Dasaratha, in the Barabar caves. The monolithic rail at Sarnath in grey and polished Chunar sandstone has been erected under the patronage of emperor Ashoka himself. Its architectural form is similar to the rails of Bharhut stupa and must have been literally transferred into stone from contemporary wooden originals. The plinth or the alambana, the stambhas, the horizontal bars and the coping have all been just carved out of what must have been a huge slab of stone. The altar or the bodhimanda situated at Bodhygaya is traditionally associated with Ashoka. The Bharhut altar consists of four pilasters.

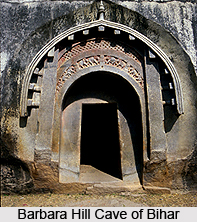

The Barabar and Nagarjuni caves are lineal descendants of similar rock-hewn caves. They are the earliest instances of the rock-cut method and are exact translations in stone of existing wood and thatch structures. The exterior walls and roofs of simple cells, including that of the Lomasa Rishi cave of the same Barabar-Nagarjuni series are highly polished which is typical of Mauryan art. The earliest of these caves is most probably one bearing an inscription dated in the twelfth year of Ashoka`s reign-the Sudama. It was dedicated to the monks of the Ajivika sect. This rock-hewn cave consists of two chambers: a rectangular antechamber with barrel-vaulted roof and has a doorway with sloping jambs. This indicates an adoption of wooden prototypes. In the long side of the chamber at the end there is a separate circular cell with a domed roof that is hemispherical. The two chambers are connected by a central interior doorway. The circular cell at the outer side has overhanging caves which are conversion in wood of thatch construction. The live rock walls are marked by irregular perpendicular grooves

In the granite Nagarjuni hill there are three more caves, each bearing an inscription of the Mauryan king Dasaratha. Among these two caves are very small consisting of a simple rectangular cell each entering from the end and having a barrel-vaulted roof. The largest one is locally know as Gopi or Milkmaid`s cave which is a long rectangular hall with a barrel-vaulted roof and with circular ends. One can enter it through a doorway that is situated in the south.

The latest and architecturally the best of the series is the Lomasa Rishi cave which though bearing no inscription probably belongs to the Mauryan period. In ground plan and general design it is similar to the Sudama cave. It also consists of a rectangular antechamber with barrel-vaulted roof entered by the long side through a doorway with sloping jambs. There is a separate cell which is oval and not round as in the Sudama cave. The facade is the most interesting architectural element in the Lomasa Rishi cave which is an exact conversion of the gable end of a wooden structure in the language of stone. The ornamentation that surmounts the gable of the facade seems to be translated from either terracotta originals or from wooden copies.

However these caves do not represent any conscious attempts towards architectural achievement. The architect of the Maurya court merely copied in stone what they saw before them constructed of wood and bamboo and clay. The facade of the Lomasa Rishi proves that there was no careless work permitted in the actual cutting of the stone. Every detail is precisely chiselled. These rock-cut chaitya halls represent the earliest extant remains of and perhaps the second stage in the evolution of this type of Indian monuments.