Measurement of intervals in Indian Classical Music was described at length by Bharata in his Natyahastra. The Natyashastra is taken as the most important work on the Indian arts, particularly theatre, and most of the basic precepts of Indian dance, music and theatre stem forth from this work. In this work, he describes two experiments on the Sruti and from his description it is evident that he was using harps and not fingerboard instruments.

Measurement of intervals in Indian Classical Music was described at length by Bharata in his Natyahastra. The Natyashastra is taken as the most important work on the Indian arts, particularly theatre, and most of the basic precepts of Indian dance, music and theatre stem forth from this work. In this work, he describes two experiments on the Sruti and from his description it is evident that he was using harps and not fingerboard instruments.

His first experiment defines the Pramana Sruti or the standard minimal interval. He says, that in the Madhyama Grama, the Panchama should be lowered by one Sruti by loosening of the string. The difference between the Panchamas by tensing or slackening the string is the measure of Pramana Sruti. In modern terminology this interval is equated to the difference between a major tone and a minor tone: that is comma diesis. (4-3=1 sruti; 9/8+10/9=81/80.) The extension of this experiment is that of the Chatusvarana or the `fourfold tuning`. Two harps, identical in all respects-construction, tuning, plectrum (Yadana Danda), pitch, and even the player form the apparatus. The two are tuned identically, twenty-two strings in each (one for every Sruti), to the Shadja Grama.

One of these shall be called the standard or non-variable (Dhruva) harp (Veena); the other shall be the variable Veena (Chala Veena). Now, reduce the pitch of the panchama in the Chala Veena by one Sruti such that it has the value of the Panchama in Madhyama Grama; then reduce all the other strings in this Veena, so that every one of them is one sruti lower than the corresponding note in the Dhruva Veena. That is, in effect the Chala Veena is now in Shadja Grama, but totally lower in pitch, in comparison to the standard Veena, by one Pramana Sruti. This is the first Sarana. The strings of the second harp are again lowered by one Sruti; it will be found that its Nishada and Gandhara correspond to Dhaivata and Rishabha of the Dhruva Veena. This is the second Sarana. The third step is once again a lowering of the Chala Veena by a Sruti, bringing its Dhaivata and Rishabha to the same pitch as the Panchama and Shadja of the standard instrument. Finally, the process is again repeated, bringing the Panchama Madhyama and Nishada of the Chala Veena to the Madhyama, Gandhara and Dhaivata of the Dhruva Veena respectively. This classical experiment has been one of the most discussed in Indian musicology; but it is certainly a landmark in the definition of the ancient musical scale.

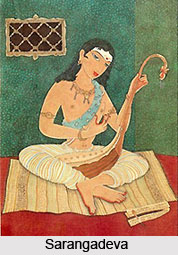

Another significant method, again using harp, was that of Sarngadeva (thirteenth century). A string is fixed on a Veena (harp) in such a way that it can produce its lowest pitch. Now tune another string slightly higher. But it must be so close to the first in pitch that a third tone cannot be introduced between them. Similarly tune a third string just higher than the second, so that there cannot be another tone between the second and the third; the process is continued thus. The strings so tuned are said to be, consecutively, one Sruti apart. It is clear, therefore, that, according to Sarngadeva, Sruti is the just noticeable difference pitch.

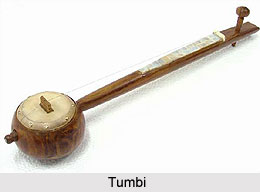

Lastly, the Veena, this time a fingerboard one, is used to define the musical scale. Hridayanarayana, Ahobala and Sreenivasa (seventeenth century) give the string lengths for various notes; in fact for all the twelve notes. This is a very important fact, the meaning of which is yet to be understood by Indian musicologists. It is a pointer to the emergence and stabilization of the Drone in Indian music.