Introduction

Terukkuttu is a form of street theatre especially in Tamil language. Terukkuttu is a form of entertainment, ritual and social instruction. This form of street theatre mainly focuses on epics like Mahabharata. Terukkuttu when plays Mahabharata concentrates on the character of Draupadi.

Terukkuttu is a form of street theatre especially in Tamil language. Terukkuttu is a form of entertainment, ritual and social instruction. This form of street theatre mainly focuses on epics like Mahabharata. Terukkuttu when plays Mahabharata concentrates on the character of Draupadi.

The word Terukkuttu is derived from "Teru" which means street and "kkuttu" means theatre. Thus the word Terukkuttu means street theatre. Therrukkuttu is not more than two or three centuries old. The Terukkuttu is thus bracketed within the Piracankam, and the Piracankam is bracketed within the full cycle of temple ceremonies.

Terukkuttu plays concentrates on the epic of Mahabharata. Even in the plays depicting the stories of Mahabharata they concentrate on the character of Draupadi. The Terukkuttu plays also perform on the stories of Ramayana.

The street theatres of Tamil Nadu include song, music, dance and drama. The actors generally put on colourful drapery. The various musical instruments which are used by the actors are drums, harmonium and cymbals.

Generally a Terukkuttu play ends usually with the completion of the war. The Terukkuttu dramas themselves can thus provide a "nine nights`" worship. Rather than nine being counted as half of eighteen, it would be more correct to say that eighteen is the equivalent of ten (or nine) as the appropriate length of a festival celebrating the goddess through the Mahabharata. In this respect, it is also highly significant that within the Draupadi cult, it is the Terukkuttu that frequently provides the counterpart to this most pre-eminent of royal rituals.

Origin of Terukkuttu

Origin of Terukkuttu was in the Gingee area. The earliest references to Kuttu, involving the nominal forms kuttar or kuttan as "performer of Kuttu," are found in the Cankam poetry anthologies and the Tolkappiyam, the treatise on grammar and poetic conventions that was probably completed a few centuries after the anthologies. While the Sanskrit term nataka also came to be used in this period, defining in the Tolkappiyam the more technical sense of theatrical drama, kuttar referred to specialists in certain "ritual performing arts" , "professional actors who were also known for their nomadic character", "a particular group of bards" with a "knowledge of stories" that they enacted . The Cilappatikaram widens our scope on this early period in its depiction of various danced enactments of episodes from the mythologies of Murukan and Krishna, which can also be included under a broad but rather loose definition of Kuttu. But it is impossible to trace anything resembling the present Terukkuttu to this period, much less an epic-related dramatized mythology.

During the Chola period, inscriptions mention that plays glorifying the Chola kings were performed at temple festivals in Thanjavur. But it is not until the Nayak period, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, that one find reference to various forms of folk drama. Among these is the Kuravanchi, offshoots of which are included in the Mahabharata repertoire of the Terukkuttu. It is possibly during this period that a repertoire of Mahabharata plays began to crystallize in the Gingee area for use at Draupadi festivals. It is estimated at around 1600 the beginnings of a Tamil ballad tradition that includes among its earliest productions a number of ballads on Mahabharata themes. As this repertoire of ballads grows, virtually all of its title episodes, including some drawn from folk Mahabharata traditions, come to have their counterparts in the Terukkuttu. Another clue that the Terukkuttu repertoire was shaped during this period is the fact that certain early Kuttus are called Yaksaganas. Indeed, though Yaksagana survives as a comparable drama form in the neighbouring Kannada-speaking state of Karnataka, Yaksaganas were also composed in both Tamil and Telugu. The use of this term in all these languages suggests that the Tamil tradition could have adopted it as an equivalent to Kuttu during the Nayak period, when mutual influences between the three language areas were greatest.

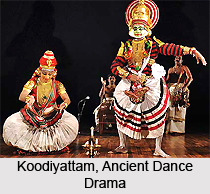

The relation between Terakkuttu and other neighbouring regional drama forms not only the Yaksagana but the Kutiyattam and Kathakali of Kerala, the Vithi Natakam of Andhra Pradesh, and the Nattukkuttus of the Tamil speaking Batticaloa area of Sri Lanka has been noted by various scholars. The prominence of the two epics, and especially the Mahabharata, in these regional drama forms suggests that the epics had a sort of "prototypical" significance for them. Though generalizations on this point are risky, it would seem that at least three of them-the Kathakali, Yaksagana, and Terukkuttu drew on epic traditions that had developed in vernacular forms during the Vijayanagar and Nayak periods, with the first known dramas probably composed during the seventeenth century. There are, of course, certain themes that are distinctive to this South Indian epic mythology, most notably concerning Draupadi`s hair. But it is doubtful that there is a coherent folk epic prototype outside the Sanskrit epics themselves.

Against such a background of regional mythologies and vernacularizations of the epics, the Mahabharata repertoire of the Draupadi cult Terukkuttu is distinctive on two fronts. First, it is a specialization within the genre of Kuttu itself. Terukkuttu has this Mahabharata repertoire only in the Draupadi cult core area. In more southern parts of Tamil Nadu excepting the very Deep South, a non-epic Terukkuttu repertoire has been shaped around other local deities and cults. In Kerala the ritual possession dances of the Teyyam cult are also called Kuttu.

The most distinctive fact about the Draupadi cult Mahabharata of the Terukkuttu is that it seems to provide the only case where one of the epics is dramatized specifically in relation to an epic-defined cult. Kathakali is most often performed at temples of Bhagavati, in Kerala a name for Kali. Yaksagana performances are often held at various goddess temples. Terukkuttu plays on the Ramayana are performed in the Draupadi cult core area at Mariyamman festivals. It is, of course, significant that the epics so often provide the primary material for dramatization at festivals for regional "folk goddesses." But again, it is in the Draupadi cult that this connection undergoes its most intense mythologization around the figure of the epic heroine as goddess.

The professional groups refer to Terukkuttu purely as kuttu, and regard the denotation of teru "street" kuttu as derogatory. They act and dance as they walk. The fact that they are part of a procession moving along a `street` or by way is what is truly designated by the prefix `teru`.

Theme of Terukkutu

The terukuttu performances centre around the enactment of stories from Mahabharata thereby emphasizing on the role of Draupadi. Plays on Ramayana are performed at Mariyamman festivals.

These plays are generally a part of ritual celebrations that also include the twenty-one day temple festival starting in Chittirai, the first month in the Tamil calendar. The terukkuttu performances continue till the morning of the second last day.

The major themes include: marriage of Draupadi, marriage of Subhadra, Marriage of Arjuna with Alli, promise of Draupadi, Arjuna`s penance, mission of Krishna, Abhimanyu`s defeat, Karna`s defeat, Battle of the Eighteenth Day and the sacrifice of Aravan in the Battlefield.

Style of Terukkutu

Terukkuttu plays comprises of song, music, dance and drama. Colourful costumes are worn by the actors. The musical instruments are harmonium, drums, a mukhavinai and cymbals.

At the courtyard of the temple an acting ground is marked out where people crouch on the three sides of the rectangular arena. The chorus of singers and the musicians stand on the rear side of the stage and the actors use the front side. Two persons hold a curtain and enter the arena, with an actor who has been dressed as Lord Ganesh, the elephant-headed Hindu god. The chorus begins an invocation to Ganesha and prayers are offered to several other deities. Thereafter the narrator appears on the stage. Kattiyakkaran relates the story and introduces the characters. At times the characters introduce themselves. Kattiyakkaran links the scenes, provides context to the happenings on the stage and joke between the scenes. Each song is rendered in a raga that is preceded by viruttam. Thereafter an actor delivers a speech based on that song.