Mughal emperor Aurangzeb was virtually that last ruler of the Mughal Empire, who would have governed in a manner, which already had begun to show signs of downfall and degeneration. Mughal architecture under Aurangzeb was an instance of being austere and minimal in each attempts. Indeed, being the son of Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb was much anticipated to balance the scale of perfection in both terms of administration and architecture - the current emperor was hugely unsuccessful in both. Though known to possess an out-and-out religious bent of mind, the construction of mosques during Aurangzeb was quite a humble and neglected an attempt. Aurangzeb`s mosques are not much acknowledged in public in present Indian times, who suddenly had shifted his capital from Agra to the Deccan.

Mughal emperor Aurangzeb was virtually that last ruler of the Mughal Empire, who would have governed in a manner, which already had begun to show signs of downfall and degeneration. Mughal architecture under Aurangzeb was an instance of being austere and minimal in each attempts. Indeed, being the son of Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb was much anticipated to balance the scale of perfection in both terms of administration and architecture - the current emperor was hugely unsuccessful in both. Though known to possess an out-and-out religious bent of mind, the construction of mosques during Aurangzeb was quite a humble and neglected an attempt. Aurangzeb`s mosques are not much acknowledged in public in present Indian times, who suddenly had shifted his capital from Agra to the Deccan.

Early during emperor Aurangzeb`s reign, the harmonious balance of Shah Jahani-period architecture was hugely rejected in favour of an increased sense of spatial tension with an emphasis on height. Stucco and other less expensive materials emulating the marble and inlaid stone of earlier periods cover built surfaces. Immediately after Aurangzeb`s accession, the use of forms and motifs such as the baluster column and the bangala canopy, earlier reserved for the ruler alone, are found on non-imperially sponsored monuments. This suggests both that there was relatively little imperial intervention in architectural patronage and that the vocabulary of imperial and divine symbolism established by Shah Jahan was grossly devalued by Aurangzeb, answering for the difference of the religious construction of mosques under Shah Jahan and mosques during Aurangzeb. At the same time architectural activity by the nobility had proliferated as never before, suggesting that they were eager to fill up the role previously dominated by the emperor, which also can be understood in the long run of mosques which were developed during and under Aurangzeb.

Contemporary histories relate that Aurangzeb had repaired numerous older mosques. The frequent mention of his repair and construction of mosques suggests that this was the architectural enterprise he most highly had valued. Aurangzeb was attentive to the maintenance of mosques. Once he had ordered a lamp for a mosque in an old outpost and on another occasion he had written to his prime minister (wazir) to express dismay that the carpets and other furnishings of the palace were in better condition than those of the palace`s mosque. Such information suggests the emperor`s spiritual links were indeed profound. The restoring of mosques during Aurangzeb during the beginning of his turbulent rule, responds to the problems.

After capturing Maratha forts, Aurangzeb often is known to have ordered the construction of a mosque. In part, they were erected from religious fervour and in part they served as a symbol of Mughal conquest. These mosques by Aurangzeb were probably constructed quickly of locally available materials. Other mosques he had built had very much filled a genuine need. For example, in Bijapur city the Mughal emperor had erected an Idgah since there was no suitable one there. In the Bijapur palace he had added a mosque for his personal use.

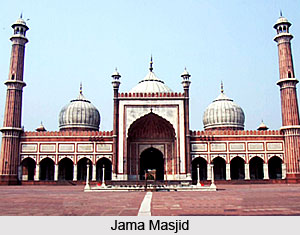

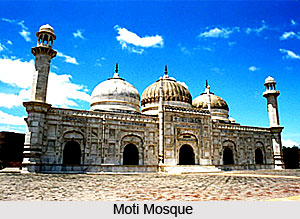

Shortly after his accession, Aurangzeb had ordered a small marble chapel, recognised today as the Moti or Pearl mosque, to be constructed inside the Shahjahanabad fort (the Red Fort of contemporary times in Old Delhi). Shah Jahan had erected no mosque inside this fort, using instead the large Jami mosque (the historic and colossal Jama Masjid nearby the Red Fort) for congregational prayers. Aurangzeb, however, had desired a mosque close to his private quarters. Five years under construction, his exquisite Moti mosque was completed in 1662-63, at considerable personal expense. It is enclosed by red sandstone walls that vary in thickness to compensate for the mosque`s angle, necessary to orient the building towards Mecca and at the same time to align it with the other palace buildings. Indeed, if one witnesses the Moti Masjid today, it comes as a brilliant dazzling instance by the Diwan-i-Am and Diwan-i-Khas of Red Fort. Entered on the east, the compound consists of a courtyard with a recessed pool and the mosque building.

Shortly after his accession, Aurangzeb had ordered a small marble chapel, recognised today as the Moti or Pearl mosque, to be constructed inside the Shahjahanabad fort (the Red Fort of contemporary times in Old Delhi). Shah Jahan had erected no mosque inside this fort, using instead the large Jami mosque (the historic and colossal Jama Masjid nearby the Red Fort) for congregational prayers. Aurangzeb, however, had desired a mosque close to his private quarters. Five years under construction, his exquisite Moti mosque was completed in 1662-63, at considerable personal expense. It is enclosed by red sandstone walls that vary in thickness to compensate for the mosque`s angle, necessary to orient the building towards Mecca and at the same time to align it with the other palace buildings. Indeed, if one witnesses the Moti Masjid today, it comes as a brilliant dazzling instance by the Diwan-i-Am and Diwan-i-Khas of Red Fort. Entered on the east, the compound consists of a courtyard with a recessed pool and the mosque building.

Although the Moti mosque and its courtyard are small, approximately 9 by 15 metres internally, the high walls, over which nothing can be seen, emphasise the sense of compact verticality creating a sense of spatial tension - a characteristic of Aurangzeb`s architecture in relation to mosques. This is further underscored by the three bulbous domes on constricted necks, the central one rising above the others. These domes were originally gilt-covered copper that resembled gold, drawing attention to the height. They later were replaced with white marble domes, still in place.

Closely modelled on the Nagina mosque, the prayer chamber of Aurangzeb`s Moti mosque, entered through three cusped arches, is divided into two aisles of three bays each with an ancillary corridor on the north for use by the court ladies. The marble surfaces here and on the courtyard walls are more ornately rendered than those on Shah Jahan`s mosques. Here arabesque foliate forms - unique during this period to imperial palace mosques - cusped arches and even architectural members are elegantly carved. They serve as a contrast to the much more sedate ornamentation of Shah Jahan`s religious edifices - a much surprising comparison between this father-son duo, who were almost at loggerheads with regards to Mughal architecture and its upholding, at times the mosques of Aurangzeb also surpassing Shah Jahan`s!

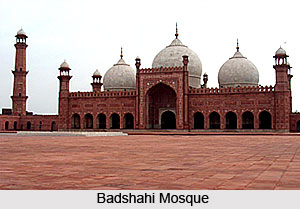

Aurangzeb`s Badshahi mosque also reveals an ornateness and emphasis on spatial tension seen in the Moti mosque, but on a much larger scale. Adjoining the Lahore Fort, the Badshahi mosque remains the largest mosque in the subcontinent (with India and Pakistan very much united in those times of Mughal Empire). An inscription over the east entrance gate indicates that it was built in 1673-74 by Aurangzeb under the supervision of Fidai Khan Koka, the emperor`s foster brother.

Aurangzeb`s mosques built in close association with palaces - primarily those dating to the time of his father, Shah Jahan - are considerably more ornate as opposed to the mosques of Shah Jahan`s reign. Their decor, however, is inspired by Shah Jahan`s palace architecture. Being a father, Shah Jahan was successful enough to influence his son deeply in terms of Mughal architectural splendour, which are thoroughly enlightened in the mosques during Aurangzeb. Ornateness formerly reserved for palaces is now found in mosques, which to Aurangzeb were the most significant architectural type. As palaces were less important to him, he had curtailed some of the earlier court ritual; for example, during his eleventh regnal year, the emperor had abolished the practice of jharoka. Significantly after this time, his most elaborate mosque, the Badshahi mosque, was built. For Aurangzeb, personal devotion and the ritual of prayer were more meaningful than courtly ritual such as the viewing of the emperor at the jharoka that had developed to bolster the semi-divine character of earlier Mughal rulers.

Aurangzeb`s mosques built in close association with palaces - primarily those dating to the time of his father, Shah Jahan - are considerably more ornate as opposed to the mosques of Shah Jahan`s reign. Their decor, however, is inspired by Shah Jahan`s palace architecture. Being a father, Shah Jahan was successful enough to influence his son deeply in terms of Mughal architectural splendour, which are thoroughly enlightened in the mosques during Aurangzeb. Ornateness formerly reserved for palaces is now found in mosques, which to Aurangzeb were the most significant architectural type. As palaces were less important to him, he had curtailed some of the earlier court ritual; for example, during his eleventh regnal year, the emperor had abolished the practice of jharoka. Significantly after this time, his most elaborate mosque, the Badshahi mosque, was built. For Aurangzeb, personal devotion and the ritual of prayer were more meaningful than courtly ritual such as the viewing of the emperor at the jharoka that had developed to bolster the semi-divine character of earlier Mughal rulers.

By contrast to the ornateness of Aurangzeb`s palace mosques is the impressive red sandstone Idgah at Mathura, also certainly sponsored by Aurangzeb. This Idgah, a mosque meant for the annual Id celebration, had replaced the temple of Keshava Deva, destroyed in 1669-70 by Aurangzeb`s command to avenge the on-going insubordination by Jats. This very factor of the Mughal ruler, of devaluing his Hindu religious builds and replacing them with Islamic architecture, had made him grossly unpopular and hated amongst his most subjects. As such, mosques during Aurangzeb are not much under discussion in present times, with much of information lost in timeline

This mosque bears considerably less ornamentation than do the other two built by Aurangzeb, but they were associated with imperial palaces. The Mathura Idgah, however, was situated nowhere near a palace. Rather, it was built at Mathura, a city then of secondary importance, on top of a demolished temple, to remind rebel forces that non-Muslims would be tolerated only so long as Mughal authority was obeyed. Perhaps such mosques during Aurangzeb and its adherence to Indo-Islamic Mughal architecture had sown the seeds to such Hindu-Muslim conflict in relation to religious builds in holy and Hindu-dominated places like Mathura, considered the abode of Lord Krishna, which also was very much visible during Babur years earlier and his construction of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya.