Indian photography had received colossal impetus during the East India Company`s advent in the early 18th century. In fact, it was chiefly due to the Englishmen that the country saw the mounting interest and curiosity in photography among the `natives`. The coinage was gradually becoming a household name.

Indian photography had received colossal impetus during the East India Company`s advent in the early 18th century. In fact, it was chiefly due to the Englishmen that the country saw the mounting interest and curiosity in photography among the `natives`. The coinage was gradually becoming a household name.

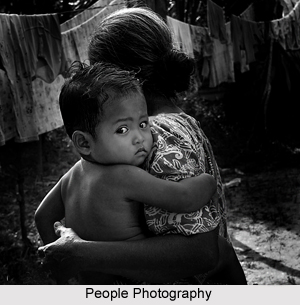

While the pattern of photography`s growth in the Indian subcontinent largely kept pace with developments in the wider world, local factors contributed to the characteristically Indian body of work: firstly, the very enormity of the country and the variety of its people provided a unique source of images. In addition, the presence of a small European population exercising political control, formed a market for particular types of work which reflected a vision of the country and its people palatable to western sensibilities and preconceptions, Indian photographers added a further dimension as they accommodated the medium to their own cultural requirements.

Mostly the photography in the early years of India was specially tied to the colonial regime. Photographers who went to India were mainly from the British government. Some photographed as amateurs, while others were actually employed to take photographs. The company actively encouraged the employees to photograph, and record archaeological sites. Thus, it was due to this that photography became a key element of the `Archaeological Survey of India`, established in 1861 (following on from the activities of the `Asiatic Society` dating from 1784) and still in existence.

Many missionaries coming from Britain to bring Christianity to India were keen and sometimes very competent amateur photographers. These few westerners in India formed the major market for photography in India and they were largely those with the money to buy photographs. Many bought photographs to paste into albums, so as to make a visual record of their visit to India, which they would take back to the home country at the end of their tour of duty.

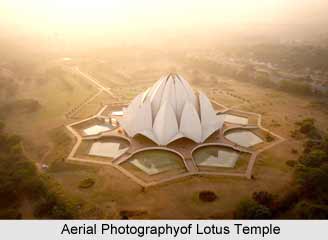

A decade later numerous photographic societies took shape to exhibit amateur and professional photographic works in all the major urban centres of South Asia. Government agencies, including the Governor-General, Lord Canning (a patron of the photographic arts), backed the use of the new technology to record the native races and tribes, architecture, military service, and life in remote areas of the sub-continent. Members of the colonial middle class adopted the cause of documenting their empire, and commercial photographers eager for livelihood entered the "native races" portraiture business.

In 1858, the East India Company "recommended that the Gentlemen Cadets, who were later to go to India, should be given some instruction in photography." In 1861 the Central Directorate of Archaeology was established by Lord Canning to inspect monuments and significant sites. Military men joined the ranks of amateurs, shooting the secular and the sacred, the artistic and the scientific. Under the authority of the colonial administration, one of the most distinctive works created within the period between 1868 and 1875. The People of India used the photographic works of these amateur photographers. But one should keep in mind that this eight volume work on racial types was created in the wake of the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 and was consequently defiled by the fallout of colonial losses which resulted in the disciplinary reconciliation of the natives.

Examples of ethnographic photography in service to the empire abound in the form of amelioration of the lot of the native, gaining personal wealth and embellishing imperial aims. Two such scientific works of ethnographic photography are the studies of Andaman Islanders conducted by E.H. Man and V.M. Portman. In 1858, the East India Company and the Crown saw the Andamans as an efficient way station on the shipping route from Southeast Asia, East Asia and Australia to India. Added to this economic component, the Crown, after the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny, needed to secure a penal colony for the mutineers - the Andaman Islands were the ideal location for such a public project. The British approached the problem of Andamanese hostility with prevailing colonial methods - `give the natives the gift of civilisation and demonstrate British technological superiority`.

In ethnographic photography, women generally appear in anthropometric poses or pictured with their spouses in life`s daily activities. In commercial photography, women as subjects were depicted in private and formal family group portraiture and were rarely shown in formal portraiture as individual subjects. Portraiture of courtesans or "nautch dancers," women of nobility or royalty, and the household servants of high-ranking women were defined in formulaic constructs.

In ethnographic photography, women generally appear in anthropometric poses or pictured with their spouses in life`s daily activities. In commercial photography, women as subjects were depicted in private and formal family group portraiture and were rarely shown in formal portraiture as individual subjects. Portraiture of courtesans or "nautch dancers," women of nobility or royalty, and the household servants of high-ranking women were defined in formulaic constructs.

However, India owes much to Samuel Bourne, who gave the professional photographers a run for their money, with his exquisite range of photographs on various genres. The Victorian living had a flare for expeditions and was fond of extensive travelling. And, for Bourne quite naturally, India existed outside the garrison towns with their easy audience of civil servants, officers and their wives. Thus, he organised lavish expeditions to the furthest reaches of the subcontinent. Bourne`s India is one of impenetrable vegetation, and forbidding mountain summits. The results are still breathtaking. On one such Himalayan expedition in 1866, he was successful to take some of the most priceless collection of adventurous photographs, which were published in the British Journal of Photography and had fuelled an escalating sense of wonderment throughout the country. The commercial photographers were the most to be facilitated. However, it was an all-accepting comment by every Britisher that to capture India through the lens was hugely dissimilar from photography in Britain. Such is the country`s diverseness.

Later on, in the 19th century, India was at the forefront of photographic development and a wide range of arresting images about India had been captured the photographers, many of which had never been seen in public before. The photographs drawn from the British Library and the Howard and Jane Ricketts Collection, reflected the major preoccupations and achievements of 19th century Indian photography. They included: the early amateurs who first introduced the medium; the documentation of India`s architectural and ethnic diversity; the achievements of commercial photographers such as Samuel Bourne; and Princely India.

Other themes included natural history, panoramas, trade and the industrialization of India and the Durbars. Since the 18th century people, events and landscapes in India had been keenly observed and documented by both Indian and European artists in paintings, drawings, aquatints and lithographs. Within a few years of its introduction in Europe in 1839, however, photography had become the new recording medium. After which, anyone could take a photograph and photography became available for the mass-market in 1901.

Since then, the colour film has become standard, as well as the automatic focus and automatic exposure cameras. And today, with the introduction of Digital cameras, the digital recording of images is becoming increasingly common in India as well.